The rather self-explanatorily titled exhibition catalog From an Imperial Product to a National Drink: The Culture of Tea Consumption in Modern India, published in 2005, may be a tad less topical today for a review, but I do believe its delightful content lends itself to discussions & sharing. The exhibition was curated by Professor Gautam Bhadra of CSSSC, Kolkata.

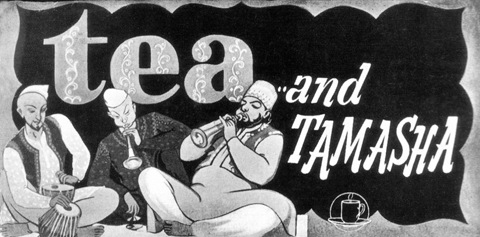

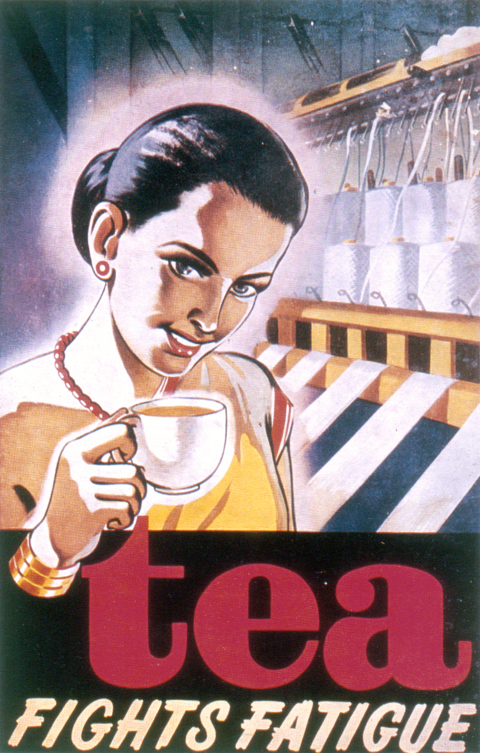

This oddly-sized booklet, refreshingly, focuses on “social practices & cultural nuances associated with the consumption of tea…” as Prof. Bhadra puts it in the introduction, “[rather] than on the oft-told narrative of political and economic struggles between labour and capital in tea production and trade”. The narrative is supplemented with relevant propaganda posters & illustrations from the times.

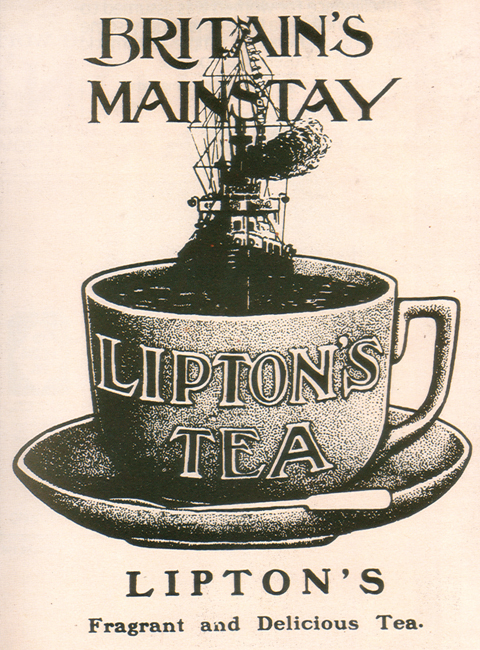

Lipton Tea Advertisement, 1913. Design: Unattributed.

In the early days of tea production by the British in India the whole enterprise bore a rather singular commercial pursuit of weakening the monopoly of Chinese tea. That was around the middle of 19th century. The narrative effectively maps the subsequent transitions of the trade from the early days when it was still mainly confined to western markets, to the following efforts by the British to warm the large Indian market up to the quaint charms of the brew, the reactionary doubts & misgivings of the locals, its gradual acceptance (first by the anglicized native aristocrats & then the clerical middleclass) as reflected in the thawing, changing tone in coeval literary & graphic produces, and finally, the surge in its popularity and its pervasion in local customs & conventions.

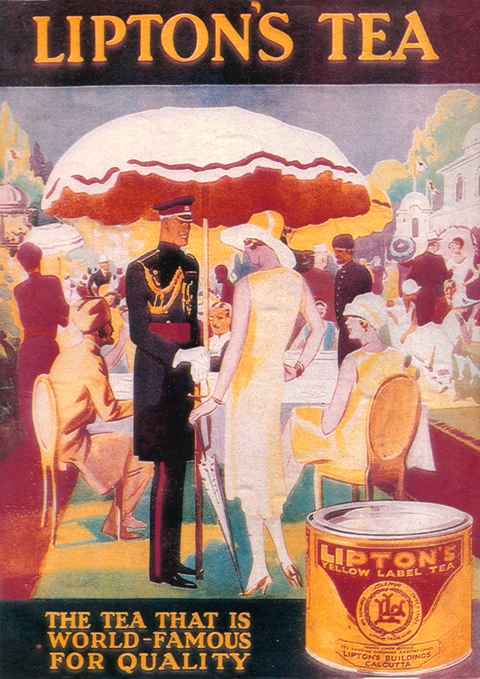

Lipton Tea Advertisement, 1931. Design: Unattributed.

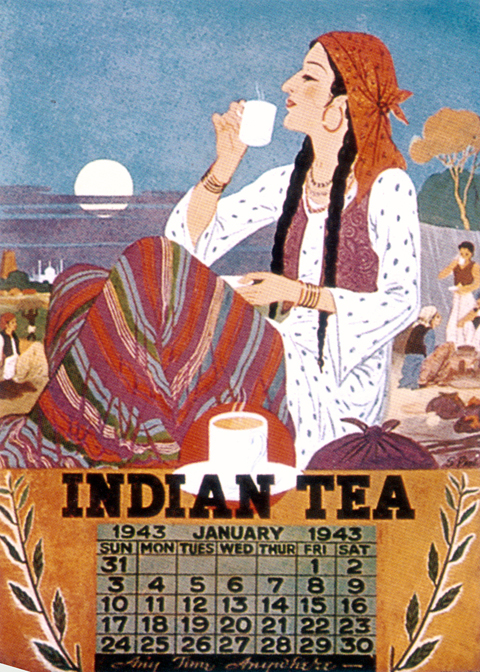

The curator spots various embedded fictions around the practice of tea consumption in different periods from a wide range of documents, including literary works: from the early days when tea is used to evoke the essence of the orient among its western consumers and its emerging associations with imperial might, to it’s later conciliation with the idea of swadeshi (when tea was accepted in popular imagination as something essentially Indian).

ITMEB Advertisement, 1942. Design: Bhagwandas Ganguly

Prof. Bhadra cites humorous passages from various literary sources that tell us that the transition was not at all very smooth and unchallenged. The native population took to tea cautiously, even grudgingly, and their counter-efforts to smear the product’s repute through alarmed satires make an amusing reading.

“A report of the early decades of 20th century suggests that a cup of tea in the morning made one a perfect Bengali gentleman, while sipping twice a day turned him into a sahib. Ceaseless craving for this new beverage, however, would brand him as a chinaman.”

People even warned how tea can make housewives addicted & wayward. Clearly, predicaments to be avoided! But the movement to popularize the product rallied on…gradually wearing these smear campaigns down. One realizes that this fascinating journey of a simple beverage begged to be narrated.

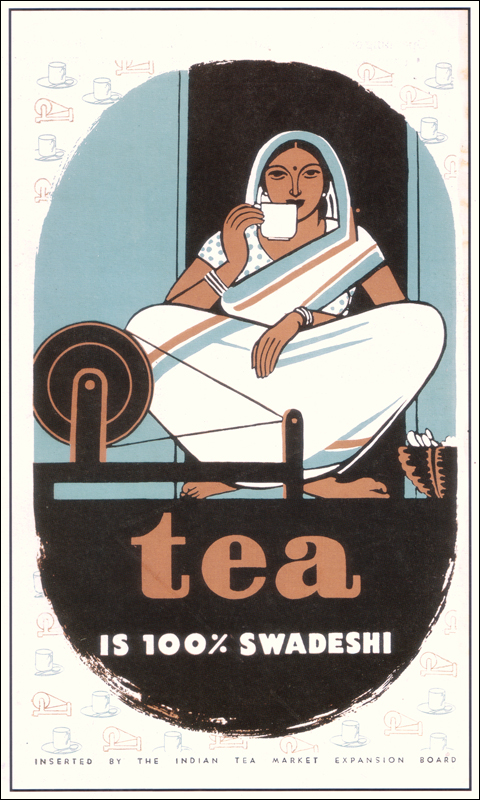

ITMEB Advertisement, 1942. Design: Subal Paul

All along, the print media & the advertisements played a vital role in shaping the ‘image’ of the product, which always appeared to bear an import beyond its immediate status as a simple beverage. In the process, as visible from the exhibits, both British & Bengali designers produced some remarkable propaganda designs which, apart from serving to illustrate the story of the beverage and its changing status, also narrate the story of graphic arts in Bengal over the ages.

ITMEB Advertisement, 1947. Design: Annada Munshi

A most exciting phase in this history is the period of political transition in the 1940s and its following decade, when with Independence & the political changing-of-guards the strategies of marketing the beverage changed too. We also know that this phase coincides with the coming of age of Bengali design, as ushered by a young crop of Bengali designers which includes the likes of Annada Munshi, OC Ganguly, Makhan Dutta Gupta & Satyajit Ray. While these designers set out to redefine design practices in Bengal, tea, the product, also needed a new definition. In 1947, we see a poster advertising tea as “100% Swadeshi”, designed by Annada Munshi.

ITMEB Hoarding, 1947. Design: Makhan Dutta Gupta.

The catalog, though itself suffering injudicious design & plagued by typesetting errors, is a delight nonetheless. The research team has done a commendable job & Professor Gautam Bhadra’s reading is masterly. I only have two very personal complaints regarding the text. First, from time to time the piece appears to be straining under the weight of certain academic trends. Here’s an example:

Desire is a problematic term, elusive & complex, possessing various meanings in different disciplines. In the context of our analysis, desire simply means a craving for something or somebody.

That such a naïve, pre-Lacanian definition of desire—though most welcome in the wake of some recent academic developments—should come preceded by such a lofty preamble may disturb both types of readers the master usually enjoys – a student of cultural studies, & the average (tea-drinking) Bengali culture enthusiast. The text suffers likewise from time to time. The writer seems no less susceptible to certain temptations than the next ill-advised scholar, straining to recreate the occult charms of theoretical writings of certain much-followed schools.

ITMEB Advertisement, 1948. Design: Annada Munshi.

Secondly, whenever the author discusses the aesthetic merit of the artworks reproduced, leaving familiar grounds of social history behind, he is found not measuring up, really, to expectations. He is brilliant in his reading of the social relations & conditions found in the materials he trains his experienced eye on. But he also indulges in little art talks, discussing spatial balance, harmony, integrative effects, and serially proposes, or endorses, hackneyed aphorisms (“…in order to be effective, images need to be affective”, for example…) that one expects not to run into in the writings of a seasoned scholar like Prof. Bhadra. At times it even impels one to wonder if the writer of this catalog finds terms like expressionistic & expressive interchangeable. One expects some semblance of the necessary academic rigor that, as we all know, makes CSSSC special.

I, however, do not wish to have it inferred that the narrative is not pleasurable; it is delightful in (spite of) itself, asides being highly informative & illuminating, and does not rank with the average jargon-jaded academic drivel we are slowly learning to accept as one of those facts of the world. It is indeed a valuable effort, and surely provokes further inquiries in many directions, not least of which is the history of graphic arts in the state of Bengal.

![]()

© Shubho Roy 2010

vasvi / 19 Oct 2010