Speaking of his illustrious ancestors, Satyajit Ray himself never hesitated to rate Upendrakishore Ray’s draftsmanship as an illustrator higher than that of Sukumar Ray.

Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury [1863-1915] was a typical 19th century Bengali polymath, who apart from being a fine writer, designer & illustrator, also revolutionized norms of printing & publication in Bengal. As a writer of children’s stories, his was a brand of humor that was more subtle & situational than absurdity, wordplay & gags that typify his son Sukumar’s more popular writings. As a result, Upendrakishore Ray is slowly, gradually, but perceptibly, being forgotten. That is alarming, because both as a writer & an illustrator, Upendrakishore’s works represent certain quaint & fragile sensibilities which I thought formed the core of the Bengali psyche.

Upendrakishore Ray’s Tunituni’r Boi [The Tailorbird’s Book, 1912] is a collection of stories for children. It is full of animals that are very, very reminiscent of people in a changing world who are no longer sure where they belong, the people that populated a Bengal that was at its ambitious best under the British rule where old class & caste structures were suddenly relaxed, allowing a wider range of aspirations: there is a dimwit tiger seeking a human bride, there is a stupid crocodile eager to have an educated progeny, a house-cat who bosses mighty tigers.

The stupid tiger with the ingredients of pithey

And then there is the eponymous protagonist of the book, Tuntuni, who is a tiny intrepid tailorbird that simply refuses to understand why the world doesn’t take it seriously. Driven by its overwhelming sense of entitlement, the tiny creature leaps from branch to branch, taking its case to one and all, demanding to be treated with respect. Written in a simple prose quivering in a controlled tremor of wit & warmth, Upendrakishore’s prose is informed by an innate musicality of lullabies.

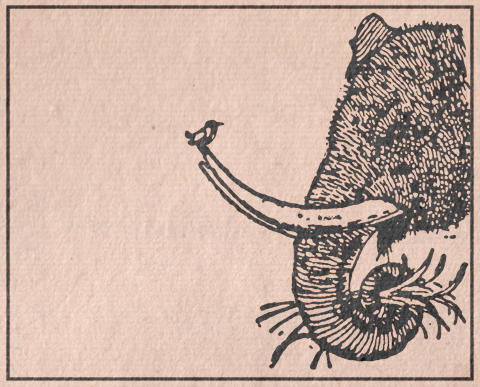

The Weaverbird & the Elephant, Upendrakishore Ray, 1912

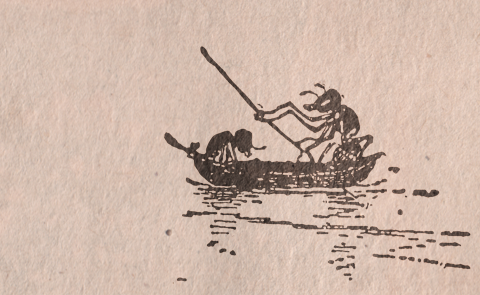

But my favorite aspect of Tuntuni’r Boi are its finely drafted illustrations. The draftsmanship displayed is of a very high order. A relaxed wit informs the frames. Some of the compositions betray the author’s unique brand of humanism not always unmingled with a studied skepticism. Then there are frames which are simply timeless: the tiny bird talking to the elephant perching on its tusk, or the distressed ant paddling a rice-husk boat taking its dying wife across the waters.

![]()

© Shubho Roy, 2010

Parvez Kabir / 22 Sep 2010